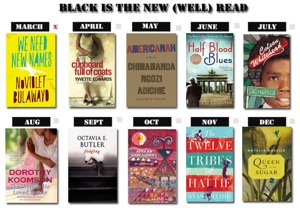

There’s nothing like a reading challenge to get your creative juices running. Maybe you have a list of authors you’ve been longing to try, or you’d like to discover some new voices. You don’t need a reason to take part in the 2014 Black Reading Challenge, just a library and the ability to read.

Don’t adjust your set, I have 10 brilliant books to brighten your year.

Plus, there’s a downloadable, printable version of the 2014 Black Reading Challenge. Pin it on a wall, stick it in your notebook, do whatever you want, but get reading!

*

March

We Need New Names – NoViolet Bulawayo

This debut novel centres around 10-year-old Darling, a girl growing up amidst the political decay and social devastation of Zimbabwe. Darling gets the chance to live with her aunt in America but discovers that along with new opportunities comes a deep longing for home. A brilliant novel that’s been nominated for every award going.

*

April

A Cupboard Full of Coats – Yvette Edwards

When an old friend turns up at Jinx’s East London home, memories she has long buried come thundering back and she’s forced to confront the tragic events that caused her mother’s death. Though the novel takes place over a single weekend, largely between two characters and in a handful of settings, it manages to traverse decades and encompass universal themes around love, envy and destiny. Be warned: the descriptions of lush Caribbean food are vivid enough to cause heartburn.

*

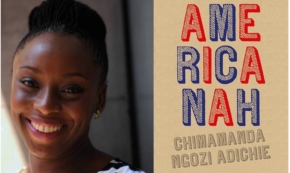

May

Americanah – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Ifemelu and Obinze are in love, but Nigeria in the 90’s is not a place where the poor and unconnected thrive, no matter how book-smart. And so they move west, to England and the US, where they discover what ‘black’ and ‘African’ mean beyond the boundaries of home. It’s a book as insightful and funny as anything Adichie has ever written, and for anyone who’s ever been a migrant it resonates again and again.

*

June

Half Blood Blues – Esi Edugyan

A black musician disappears in 1930s Germany and leaves behind an enduring legacy and a towering mystery. It’s no wonder the Canadian author scooped up a slew of awards for this work. She recreates the stifling menace of Nazi-Germany, slips into the minds of three young men and weaves around them a powerful story of jazz, brotherhood and shame.

*

July

Sag Harbour – Colson Whitehead

Take the kid from Everybody Hates Chris – sweet, articulate, perpetually narrating and analyzing – give him Cosby-rich parents and dump him in the Black Hamptons (otherwise known as Sag Harbour). Voila! You have Whitehead’s 2009 novel. It’s a clever, funny and nostalgic coming-of-age story set in a country that fears young black men.

*

August

The Woman He Loved Before Me – Dorothy Koomson

Libby has a gorgeous husband, a beautiful house and the perfect life. Until she stumbles on some diaries and begins to wonder what happened to her husband’s first wife. Prepare to be shocked, shocked and then shocked some more. There are more twists in this book than a salt shaker and Koomson leaves no emotion unplucked. Perfect beach read.

*

September

Fledgling – Octavia Butler

Dial down your prejudice button, yes this is fantasy, yes there are vampires, but this is like nothing you’ve ever read before. Shori is a young vampire with amnesia and a killer is hot on her trail. As we learn more about her past life we discover a hierarchal society based on the African village but divided along colour lines. It’s fantastic, thought-provoking and did I mention, it’s like nothing you’ve ever read before?

Warning: the story contains references to paedophilia.

*

October

African Love Stories – Edited by Ama Ata Aidoo

We don’t hear enough about love in Africa. What we hear about is death, disease and disaster. This collection of love stories spans the African continent from Sudan to Kenya to Zimbabwe and features a steller line-up of authors including Sefi Atta, Helen Oyeyemi and Chimamanda Adichie. There’s every reason to read this anthology and not a single reason not to.

*

November

12 Tribes of Hattie – Ayana Mathis

A family moves north during the Great Migration, but the dreams and aspirations that drove them from the Jim Crow south are soon replaced by equally bitter experiences. Mathis’ writing is astoundingly rich, and though this collection of stories is dripping with sorrow, there’s literary joy in every line.

*

December

Queen Sugar – Natalie Baszile

Single mother Charley inherits a Louisiana sugarcane farm and decides to abandon her city life in LA for the challenges of farming life. It’s a heart-warming story about family, female empowerment and reinvention. Perfect for the holidays.

Print off the 2014 Black Reading Challenge and check off the books as you read.